“Because all the interesting things in life were invented before you were born.”

As crazy as it may sound, Google has not yet “organized the world’s information” about Common Lisp. The best tutorials are hard to find. Here’s how I got started.

Author’s note: I started on this post before publishing my previous entry, Questions for Common Lisp Experts, so I am much smarter today about why things work they way they do in Common Lisp. However, I thought it might still be helpful for other newcomers to see how I went about getting started with Common Lisp. Some of the concepts in here feel a little too basic now, but at the time, they were a struggle to get to. In that sense, this is both a tutorial and an experience report. I would still recommend this approach.

Setting the stage

If you’re used to exploring different modern language environments (i.e. those that got their start in the 21st century), Common Lisp is daunting and unusual in a number of ways.

First of all, the term “Common Lisp” refers to a language standard, not a particular compiler or implementation. Since that standard was accepted and published, there have been many implementations created, some proprietary and some open source, and a number of them are in active use. So your first decision point is “which implementation of Common Lisp should I use if I know nothing about this language?” This is where I’ll try to help, starting with the first step.

Install roswell

Most guides direct you to a long list of Common Lisp

implementations to choose from, each of which has its own

configure, make, make install setup to build from source. But

you don’t need to build from source if you just want to start

learning the darned thing.

Fortunately, less than a decade ago, a kind soul developed the Roswell tool, which manages the whole process of fetching, building, and switching between the various Common Lisp implementations that are available via open source.

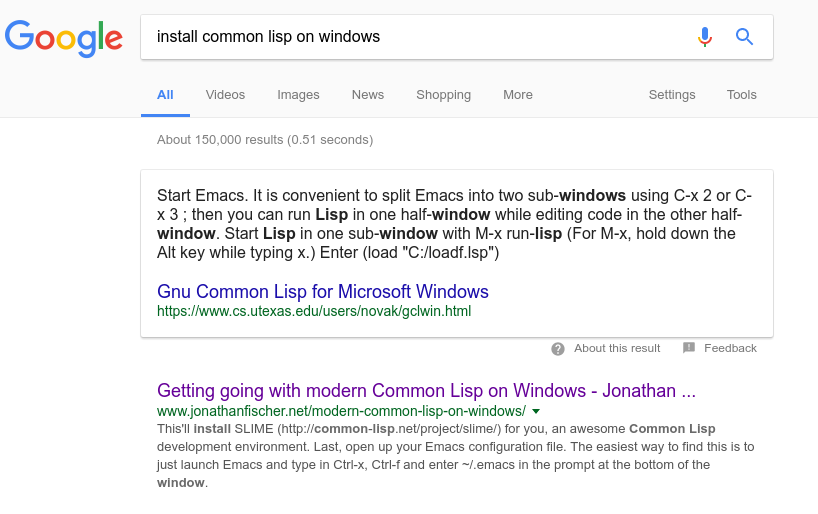

It installs basically anywhere, including Windows. (Yes, Windows. Search Google for “install common lisp on windows,” I dare you. In fact, here’s a screenshot. Does anyone wonder why people think Common Lisp is hard? Why does Google hate Common Lisp, I wonder?)

There are a couple of simple ways to install Roswell.

$ brew install roswell

Or on ArchLinux, use the yaourt tool.

$ yaourt -S roswell

Or a .zip file for

Windows.

Install Common Lisp

Once Roswell is installed, do this:

$ ros install sbcl-bin

This installs the binary distribution of the latest version of Steel Bank Common Lisp, the version that the cool kids seem to be using these days (more later).

Then, you can do things like

$ ros list installed

$ ros use sbcl-bin

And finally, to launch into the world-famous, often-imitated but never-surpassed, for (and from) the ages, read-eval-print-loop, also known as, the one and only REPL:

$ ros run

*

It’s kind of anticlimactic, isn’t it? For some reason, Roswell suppresses the banner. So, if you want:

* (lisp-implementation-type)

"SBCL"

* (lisp-implementation-version)

"1.3.19"

* (exit)

$

But nobody uses the REPL from the command line like this. You want

to use an editor with support for an integrated

REPL (notice I didn’t say emacs). See Editors.

If and when you install another Common Lisp implementation, you will

use the ros use command to select it as your default lisp. Roswell

can do much more, see the documentation.

Why SBCL?

There are lots of Common Lisp implementations to choose from, some free and some commercial, so why choose SBCL? Because it has a github repository (which is a mirror of its SourceForge repository, but at least the source is there); and it has a monthly release schedule, which means it’s being actively improved.

One of the advantages cited by Common Lisp advocates is that there are many compatible implementations of the language standard, which means you can write code and try it out on different compilers. Since some compilers emphasize different things, from type inference to optimization, this can only improve the quality of your code.

This is true, but it’s incredibly confusing for newcomers. Just start with SBCL, see if you can get productive, and then shop around for alternatives. There are definitely some interesting projects out there.

Editors

The joke is that everybody wants to try Common Lisp until they hear

you have to install emacs in step one. (I.e., see what Google

Search recommends, sheesh.) Well, you don’t.

The Atom editor is a decent choice and even supplies a plugin to get you closer to the emacs-inspired interactive editing nirvana we all dream about it.

Setting up Atom for SLIME

Author’s note: I don’t use this editor, but I did go through this process and got an SBCL REPL up and running inside Atom. (Someone on reddit recently said, “please don’t recommend Atom-Slime,” so there may still be some problems. Unfortunately, there are few open source alternatives on Windows.)

You do have to jump through a few hoops but it’s nothing like getting a remotely complicated nodejs Javascript project up and running with linting, testing, bundling, etc.

First, after installing the Atom editor, follow the instructions on this page: atom-slime

Aside from installing the Atom packages atom-slime,

language-lisp, and lisp-paredit, you need to get a copy of the

SLIME code that emacs uses for its magic.

Then, you need to set the atom-slime settings to tell it how to

launch SBCL, and where to find the SLIME you downloaded.

To repeat, since this is unusual, you need to git clone the SLIME

repo and then tell atom-slime where to find it.

Since we’re using Roswell, the “Lisp Process (Name of Lisp to run)”

setting should simply be ros. The atom-slime developers have

helpfully integrated knowledge of Roswell into their system, so

there’s no need to do the usual ros -Q run, which is what emacs

users have to do.

The “SLIME Path” setting should be the path to wherever you installed SLIME. (You did install it, right?)

After that, select Slime -> Connect from the Packages menu, wait a few seconds for the initial compilation of SLIME to complete, and you’ll see a REPL pop up.

(When I did this, it didn’t work the first time. I exited Atom, checked my settings, and tried again, and then it worked.)

Paredit, smartparens, and parinfer

I’m going to assume you already understand how to manage code in parentheses, but if you don’t, consider installing paredit or smartparents. (Parinfer is a newer choice with an innovative approach, but I find it finicky.)

If you think you’re going to manage nested parentheses without the help of a plugin, forget about it. There is no reason to do that, these days.

Setting up Emacs for SLIME

If you’re an emacs user, you know you live for the

frustration-followed-by-breakthrough-dopamine-rush of combing

through decades-old wikis or info pages to figure out how to set

yourself up, right?

Or, just install Prelude and customize it from there. Prelude gives a great out-of-the-box experience for new emacs installations. I always start there.

For Lisp, here is my personal.el file. You don’t need all of it,

but note that 1) it’s not long and 2) The SLIME-specific settings

are at the bottom. The main thing is you want to set

slime-lisp-implementations. SLIME supports switching between

multiple implementations, but we’re using roswell for that, so no

need.

(prefer-coding-system 'utf-8-unix)

(with-eval-after-load 'prelude-custom

(setq prelude-whitespace nil)

(setq prelude-flyspell nil))

(with-eval-after-load 'slime

(slime-setup '(slime-fancy slime-banner slime-repl-ansi-color))

;; indentation tweaks

(put 'define-package 'common-lisp-indent-function '(4 2))

(setf slime-lisp-implementations

`((roswell ("ros" "-Q" "run"))))

(setf slime-default-lisp 'roswell))

(add-hook 'text-mode-hook 'turn-on-auto-fill)

(add-hook 'lisp-mode-hook 'turn-on-auto-fill)

prelude-modules.el

Prelude comes with most batteries included. It uses a file called

prelude-modules.el, which you place in your ~/.emacs.d/ folder,

to load language-specific extensions.

Unfortunately this file is not installed by default. What you want to do is install it, and then enable the common lisp extensions.

$ cd ~/.emacd.d

$ cp sample/prelude-modules.el .

Then edit ~/.emacs.d/prelude-modules.el, uncomment the

prelude-common-lisp line, and restart emacs. It will download and

install the necessary packages emacs needs to get you on your lispy

road at startup.

Portacle

If you’re not looking to set up a long-term development environment and just want to give Common Lisp a try, take a look at Portacle. It’s a one-click installer that even works on Windows, that gives you an emacs editor along with a recent version of SBCL. There’s a big fat red warning on its home page, which is why I steered away from it. But the Windows installer does work.

Getting libraries

You want to npm install but since Common Lisp standardized before

npm was even conceived, it’s not quite that simple. There are two

tools you need to know about to get libraries: quicklisp and

asdf. Don’t google them yet: you’ve already got them, since asdf

is bundled with SBCL, and quicklisp is bundled with Roswell.

The first thing to know about these tools is that they aren’t command-line tools. They are programs that run inside your REPL. Apparently there was a time when people thought Common Lisp would become an operating system and command-line shells would be made obsolete. See, history is fascinating. (There are people still working on this idea, by the way. Go check them out, it’s wild.)

Quicklisp

Quicklisp is like clojars or the npm registry. It’s a distribution site for slightly vetted libraries. One of its major drawbacks is that it’s only updated monthly, but in some sense it’s an advantage, because the libraries it includes have generally been stable for years.

This approach also encourages library authors to maintain backwards compatibility, which if you agree with Rich Hickey’s complaints about Semantic Versioning, is probably a good thing.

So when you want to download a library from the web, you first fire up your REPL, then do this:

CL-USER> (ql:quickload :alexandria)

to load the most-used, practically mandatory Alexandria library.

Quickload will take care of downloading your libraries and loading them into your repl. This is fine if you’re playing with code in the REPL. But what if you want to build a library or application yourself?

ASDF

ASDF loads code from your local disk into a running Lisp image. It’s also the way you configure your libraries for sharing with other projects.

The terminology used in Common Lisp was invented in the 18th century, so bear with me here.

A package is what we would call a module or a namespace today.

Outside Common Lisp, a common approach is to combine loosely-coupled

modules together into a program, and to use one file per module.

This approach translates to using a single Common Lisp package per

file.

However, this is not how Common Lisp libraries have been developed, historically. The standard allows for different approaches, so see this StackOverflow question and answer for more background.

Personally, I find the use of a single global namespace makes it difficult to separate concerns, even if Common Lisp does not strictly enforce information-hiding. So I tend to stick with the one-file-one-module/namespace/package approach.

Next, a system is what we would call a library or an

application today. It’s a collection of source files that

represent packages, plus additional things like test files,

documentation, etc.

Systems are defined in .asd files using the defsystem form

provided by ASDF. Like most things, including Clojure, Node, etc,

getting this file right is a bit of a pain in the neck until you

learn it.

There is a tool called

quickproject designed to

help with this. It’s not exactly as easy as the various

template-driven get-started-with-a-new-project things out there, but

it’ll at least ensure your initial defsystem form is correct, and

you can edit it from there.

An example

Here is the .asd file from a library project I’m working on. It

makes use of ASDF’s package-inferred-system scheme, which I gather

is ASDF’s way of supporting the one-file-one-package approach. The

main benefit is you don’t have to enumerate your source files,

because ASDF finds them in the current directory, and finds

transient dependencies by reading your defpackage or

define-package form.

(defsystem :anticrisis.retro

:name "It's back to the future all over again."

:version "0.0.1"

:license "MIT"

:author "https://github.com/anticrisis"

:class :package-inferred-system

:depends-on (:alexandria

:named-readtables

:bordeaux-threads

:local-time

:anticrisis.retro/core

:anticrisis.retro/readtable

:anticrisis.retro/user)

:in-order-to ((test-op (test-op :anticrisis.retro.dev))))

In this system, I use the Clojure-esque approach of implementing

functionality in separate namespaces (which don’t need to be listed

here), and importing/re-exporting them from a core package. Again,

the nice thing is I don’t generally have to touch this file when I

create new source files.

There is probably need for a complete tutorial on how to do this.

Version numbers and dependency management

Apparently the Common Lisp community doesn’t generally explicitly depend on library version numbers. Now, I happen to know for a fact that the whole idea of version numbering existed before Common Lisp was standardized, so I’m not sure what the reasoning here is. I suppose it encourages library writers to always maintain backward compatibility, which is a great thing. But it is confusing for people coming from other library ecosystems.

ASDF does support declaring dependencies on external libraries with specific versions. But few projects seem to use that, and it isn’t obviously clear how that would work with Quicklisp.

Fortunately, there is a Common Lisp tool called

qlot that aims to provide

project-local dependency management in the style of npm.

For more background on the traditional approach to packages in Common Lisp, including a detailed explanation from Rainer Joswig (who is the single most dedicated and helpful Common Lisp expert publishing regularly), see this Stackoverflow question.

Directories

Ok, so you’ve installed Roswell, you’ve learned about Quicklisp and

ASDF, and your home directory now has a few new . directories.

The most important thing to know right now is how to get ASDF to find your source code when you want to load it up.

Firstly, if you’ve used ql:quickload to get it, there’s nothing

else you have to do. ASDF and Quicklisp work well together.

This is mainly about code you’ve written yourself, or code which isn’t available in Quicklisp.

If you don’t really care where you put your code, just put it in

directories under ~/common-lisp/ in your home directory, and ASDF

will find it. When ASDF starts up, it makes a catalog of every

.asd file it can find under that home directory. (This means, by

the way, that if you add new .asd files or systems, you need to

reset ASDF. The simplest way to do that is to restart your REPL, but

there are also ASDF commands. Unfortunately, I always forget which

command is which, and restarting the REPL takes about a half-second,

so that’s what I do.

(By the way, if you’re on Windows, your home directory might be in

\Users\you\AppData\Roaming\ or \Users\you. I use Windows and I still

can’t figure out why sometimes it’s one or the other.)

If you’re more particular about your directories, you may need to make this file and put it in your home directory. (This, I haven’t tested on Windows.)

~/.config/common-lisp/source-registry.conf

(:source-registry

(:tree (:home "dev/common-lisp"))

:inherit-configuration)

This file tells ASDF to look for code under my ~/dev/common-lisp

directory, because I like to pretend there are non-dev things I

might use my computer for.

Roswell and Quicklisp directories

The .roswell directory has a pretty complex organizational system,

because it needs to manage multiple Common Lisp implementations (and

versions of them) as well as Quicklisp. So you might have to hunt

around in there.

Some guides tell you to use local-projects in the Quicklisp

directory. If you put symlinks to your projects in that directory,

Quicklisp will “load” them from there instead of the Internet. I

don’t use that, but apparently there use to be something called

“symlink farming” which apparently was quite popular.

References

- For other great beginner resources, see the sidebar on /r/lisp.

- Top Google search result for “common lisp” is

common-lisp.net, which was last updated in 2015, so there’s that. (And I’m not linking to it so it doesn’t get more pagerank juice, because this one blog will make all the difference.) - Rather than the “official” home page, see this independent one: lisp-lang.org

- There is no better learning resource about the language, as opposed to the development environment, than Practical Common Lisp.

- Quickdocs is the place to go to browse through the libraries available in Quicklisp. It’s also a handy way to see who depends on which libraries, which can be a proxy for stability and reliability.

- A good curated list of libraries to reach for is the 2015 State of the Common Lisp Ecosystem report. Another (a bit less curated) is Awesome Common Lisp.

- The definitive (well, almost) ANSI Common Lisp spec is available

online at something called the

HyperSpec.

It may make your eyes bleed because it was typeset in the 90s and

has an overly restrictive license that prohibits anyone else from

improving it. (Why, oh why? Someone should write a letter). There

is no better comprehensive resource online, unfortunately, and

once you get used to every other word being an underlined

hyperlink (wow, if you use your pointing device and click the

word, it takes you to another page!), it can be quite helpful to

understand the finer points of Common Lisp.

- The best way to use the HyperSpec is to use Google to search

for, for example,

CLHS remove-if-not. If you use emacs/SLIME,C-c C-d hwill get you to the HyperSpec even faster, for all those times Google doesn’t load. (Thanks to Grue for pointing this out.) - If you can’t read the website because of eye damage, keep trying. Amazingly, after a few weeks of repeated exposure, I can now actually read it.

- The best way to use the HyperSpec is to use Google to search

for, for example,

- On the other hand, the Common Lisp Quick Reference is a beautiful document, lovingly crafted, and designed to be printed by one of those machines that puts ink on paper. Ok, so the “quick reference” is 53 half-pages including a comprehensive index, but this is Common Lisp we’re talking about! Seriously, though, this is really an excellent reference. Print it out, put it in your laptop sleeve, read it on the train, bus, plane, wherever. You won’t regret it.

Final words

Common Lisp, like all Lisps, rewards those who invest the time to learn. I hope this little guide helps at least one person save a little time with the boring stuff so they can get to the good stuff.

Comments are always welcome and are on reddit.

Updates

From comments and messages I’ve received since originally publishing this, let me add the following:

- Another project template skeleton is cl-project, which adheres to the practice of one-file-one-package, and includes the boilerplate needed for unit testing. (Thanks to dzecniv.)

- I left out the Common Lisp Cookbook, because I hadn’t run across it in my initial setup exploration.

- For a video guide to installing Emacs and SBCL on Windows, see this video from Baggers, who also live-streams his coding sessions regularly.